|

|

|

|

||||||||||

The magic-lantern -- the first projector -- was invented in the 1650s, and soon became a showman's instrument. By the end of the 17th century, wandering lanternists were putting on small-scale shows in inns and castles, using a lantern lit with a feeble candle. Often these shows featured goblins and devils -- hence the name the "magic lantern."

| An early showman carries his magic-lantern and slides on his back. |

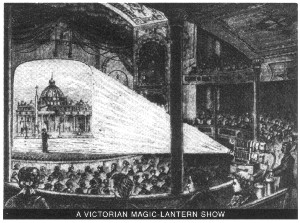

By it's heyday at the end of the Victorian period, magic-lanterns were everywhere -- in homes, in churches, in fraternal lodges, in schools, in large-scale halls and theaters, and as a regular part of home and public entertainment. At that time there were probably between 30,000-60,000 lantern showmen in America, giving between 75,000 and 150,000 shows a year.

Lanterns came in all sizes and shapes, from toy lanterns for children, to those used in large halls -- huge brass-and-mahogany, double-lens machines lit with "limelight." The limelight was created when oxygen and hydrogen were squirted on a piece of limestone which turned incandescent once the gases were lit, and produced a light as powerful as that in a modern movie projector. The lantern projected hand-colored slides on a full-sized screen.

The slides -- many of them animated or capable of exotic special effects -- changed every 30 seconds or so, and illustrated stories and songs and comedy, just as the movies would later. In America, the foremost magic-lantern artist was Joseph Boggs Beale, who produced over 2,000 images for the lantern.

As the slides were projected in a theatrical magic-lantern show, a live showman and musician provided the "soundtrack," and the audience joined in creating sound effects, playing horns and tambourines, and clapping, cheering, and booing, just as in the melodramatic theater of the day.

Though not the first such show, one of the best known of early shows was the Fantasmagorie (Phantasmagoria in English) -- the forerunner of the Halloween Show. It was produced by a Belgian, E'tienne Gaspard Robert, who called himself Robertson. At first Robertson simply gave scientific demonstrations with his lanterns. But upon discovering the French public's appetite for the macabre in the declining years of the Revolution, he opened an elaborate ghost show in Paris in 1799.

| The audience reacts in delighted terror at the 1799 Phantasmagoria magic-lantern show in Paris -- the ancestor of today's Halloween horror movie. |

The Phantasmagoria was held in an old convent that was converted into a magic-lantern theater. Dark passages decorated with mysterious pictures and the bones of dead monks led the audience to a catacomb hung with black velvet and lighted by a single lamp. The audience sat facing a screen behind which Robertson's magic-lanterns and assistants were hidden. He began by discussing "in scientific terms" the sensations created by thoughts of phantoms and witches.

Suddenly the lamp went out. Thunder roared and lightning flashed. Church bells tolled, the lightning and thunder increased, and a tiny figure -- half-human, half-demon -- appeared in the air, shimmering and ghostly. Gradually the figure seemed to approach, growing larger and larger, until suddenly it disappeared with a wail. Bats fluttered on the walls, ghosts and goblins groaned, skeletons came hurtling toward the audience.

Women who had come to the show fainted in terror. Bold men hid their eyes.

The show was a smash success -- the toast of Paris.

Robertson's performance was staged with the help of several magic lanterns and six assistants, all hidden behind the screen, on which the images were rear-projected. To make the images change size, Robertson used lanterns fitted with special self-focusing lenses, and mounted on large wheeled platforms. The lanterns could move backwards from the translucent screen, making the goblins and skeletons appear suddenly larger, as though they were moving toward the audience. Other images were projected on smoke, which make them swirl magically. Others were projected on the walls with hand-held lanterns, so that bats could flicker in the corners and dive-bomb the women's hair.

Robertson imitators were soon performing all over the continent, and throughout the coastal United States as well. The first Phantasmagoria show in America, in New York in 1803, was only four years after Robertson's show in Paris.

Half a century later the Phantasmagoria was still going strong. Joseph Boggs Beale, the man who would later become America's leading magic-lantern artist, saw a Phantasmagoria show as a young man in Philadelphia during the 1850s.

The Phantasmagoria intensified the tradition of ghost and goblin shows from the lantern's early days of the wandering showmen, and led to a whole genre of macabre magic-lantern slides. By the nineteenth century this genre was a standard part of the repertoire of the magic-lantern showman who traveled the country, playing in theaters great and small. Some of these bizarre slides showed terrifying figures of the underworld, some were "dissolving views" in which beauty was transmogrified into beast, and some were moving caricatures -- the first animated cartoons.

| The Ratcatcher an animated comic slide, uses two pieces of moving glass. |

The most popular of the animated cartoons was the notorious Ratcatcher: A man lay asleep, snoring vigorously, his jaw moving up and down as the audience made the sound effects. Suddenly a rat appeared, made a dash for his mouth, and was swallowed in a gulp. The audience -- in the midst of creating the snoring sound effects -- gulped, gasped, sputtered, and roared.

The magic-lantern shows that toured to theaters in the nineteenth century tended to be "variety bills" because "variety" cast a wide net, and because few lanternists could afford to purchase (or to cart) the equipment needed for several special shows. But lanternists often changed their featured segments to fit the occasion, and no doubt the macabre genre was especially emphasized at Halloween, as that holiday gained popularity at the end of the century.

| A giant bedbug terrorizes a Victorian gentleman in one of the bizarre Halloween slides created by Joseph Boggs Beale. |

The Halloween Magic-Lantern Show developed by the modern-day American Magic-Lantern Theater draws upon this long lantern tradition. It uses "front projection," an original 1890s "bi-unial" magic-lantern, and antique slides hand-painted by Joseph Boggs Beale. The show features the popular spooky tales of the period, blending ghost stories like "Little Orphan Annie," horror tales like Poe's "The Raven," bizarre music hall songs like "Don't Swat Your Mother, It's Mean" and, of course, animated cartoons, . . . including the ever-disgusting, ever-hilarious Ratcatcher.

One of the most elaborate nineteenth century magic-lantern shows, and the one that was the forerunner of many Christmas magic-lantern shows to come, was that at the Royal Polytechnic Institute in London. The Polytechnic, the equivalent of our modern combination of science museum and IMAX theater, was a museum that contained a large theater specifically designed for elaborate magic-lantern productions.

From 1838 to 1876, the Polytechnic produced extraordinary shows that dazzled two generations. The shows used giant lanterns with slides that were sometimes two feet long. Over 900 "Polytechnic" slides were exquisitely painted by the specialist firm of Childe and Hill, and Childe's dissolving views and elaborate special effects were an important part of the shows' popularity. The program was changed regularly during the year and included battlefront reports of the current wars, and fairy tales such as "Aladdin's Lamp." The highlight of the year was The Christmas Special, featuring (of course) Dickens' classics like "Gabriel Grubb."

The Christmas theme was also an obvious one for the lanternists who traveled from hall to hall in America during the nineteenth century. Often, as with Halloween, they would turn their "variety show" into a "Christmas Show" by featuring Beale's illustrated sets of Christmas stories like "A Christmas Carol," or "The Little Match Girl" and illustrated Christmas carols.

As a young man in the 1850's, Beale himself attended several specifically "Christmas" magic-lantern shows in Philadelphia church halls, but he also commented on one generic Christmastime Special show that he saw in December, 1860. The show was a actually a travelogue, a format which was to become one of the most popular kinds of magic-lantern entertainment, and which made full use of the new limelight "stereopticon" (double lantern) technology and the newly developed process of transferring photographic images to glass slides:

| A nineteenth century magic-lantern show, using the "stereopticon" (double lens) magic-lantern, lit with limelight. |

| This evening Pa, Ma, Aunt Harriet Cox, Aunty Boggs, Steve, Louey, & I went to Concert Hall to the "Stereopticon," a new exhibition, a little like [the old] magic lantern but much more powerfully lighted. The pictures are all taken from nature & are transparent photographs on glass, & are pictures for the stereoscope. By this new instrument they are thrown on a large canvas containing 600 square feet. The pictures are from all parts of the world, especially Europe, & some are shown much larger than reality; so that they appear on most too grand a scale; such as ladies & gentlemen, 10 feet high, looking at Niagara falls. The Hall was crowded, & the audience seemed to be very much pleased, & gave extra applause when familiar places were shown. . . . |

The recreated Victorian Christmas Show of the American Magic-Lantern Theater is like the Polytechnic Show -- an entire show with a Christmas theme, using Beale's hand-painted slides. It features "The Night Before Christmas," "The Little Match Girl," "A Christmas Carol," a sequence on a "Civil War Christmas," illustrated carols like "O Holy Night," and animated Christmas cartoons.

The Victorian Christmas Show demonstrates Beale's mastery of the magic-lantern -- a medium for which he created a vast repertoire of illustrated stories and songs. His work was part of his publisher's effort to make great literature, history, and religion available on screen to a wide audience, a project that continued from about 1880-1915. (This opus forms the core of The American Magic-Lantern Theater's shows, and allows it to produce its ten different full-length productions.)

| Joseph Boggs Beale (1841-1926) was America's foremost magic-lantern artist. |

The genius of Beale's slides is partly in the way each slide

advances the story plot, providing a new, dramatic, "action image."

But supporting this central image are also details in the picture which

reinforce lines from the story. As the showman dramatizes the action,

the eye of the viewer moves within the picture, picking up details as

they are mentioned, becoming like a latter-day movie camera, zooming

in here, panning there, building texture toward the next dramatic moment.

| One of a set of slides for "The Night Before Christmas," drawn by Joseph Boggs Beale. Note the combination of story-telling "action image" and attention-holding detail. |

This proto-cinematic effect is heightened by sequences of slides that not only track the action, but move the "camera angle" or point of view, shifting perspective to emphasize psychological points. Dissolving images, close-ups, fades, cross-editing of story-lines, etc. are all part of Beale's artistic repertoire for telling stories on screen. It is no wonder that his slides became the most popular in the country, and were reproduced in the millions for home and professional use.

But for all Beale's skill, he could not compete with the movies, once its producers stopped simply demonstrating the medium's novelty, and began using it as the magic-lantern was used -- to tell stories. With the advent around 1905 of both a successful movie thriller, "The Great Train Robbery," and inexpensive movie "nickelodeon" theaters, the magic-lantern quickly declined as an entertainment medium, relegated to illustrating the songs sung between the reels of the early movie features, or as a single act in vaudeville shows, or to educational functions.

The child, the movies, had killed the parent, for the magic-lantern was truly the "father of film," -- providing not only the basic optical projector, but a vast artistic repertoire of on-screen visual story-telling techniques, as well as a time-tested repertoire of story content for the early movies.

Only in recent years has the magic-lantern show returned, with recreated shows like those of The American Magic-Lantern Theater. Modern audiences are of course accustomed to the elaborate special effects of today's movies and videos and computer games. But they seem to have no trouble slipping back into the magic-lantern show's combination of live drama, live music, and on-screen image; its interplay of performers and audience; its noisy group participation. At a time when people are reaching back to the past in order to find meaning for the present, the spirit of the magic-lantern show meets a modern need, and lives again.

For the story of the Borton Family's magic-lantern

history, click here.

|

Sign-up here to Request Order

Info Upon Book Publication. |

| Repertoire | • | Schedule | • | About Us | • | Book Us! | • | What's New |

Last Update: 3/26/08 9:19

Web Author: POW·R·PC

Copyright © 2008 by The American Magic-Lantern Theater - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED